Sugar and Spice and all things nice!

How much sugar do you eat?

Sugar can naturally be found in most foods including fruits, vegetables, milk and honey but sugar cane and sugar beet are the best sources for extracting sugar on a large scale for commercial purposes.

Sugar can naturally be found in most foods including fruits, vegetables, milk and honey but sugar cane and sugar beet are the best sources for extracting sugar on a large scale for commercial purposes.

Sugar cane field

Sugar cane field

Where did sugar cane come from originally?

Sugar cane is believed to have come from Northern India over 6000 years ago. The word sugar originally came from the Sanskrit shakar meaning “ground or candied” sugar. In ancient India sugar cane juice and sugar products like gur or jaggery were used in food and drink. It was also used in Ayurvedic medicines and in religious Vedic rites and rituals. Indians introduced crystallised sugar to China through Indian Buddhist monks and across the rest of the world through Indian and Arabian merchants and sailors.

During the 14th to 19th century in Europe, sugar was considered to be the ultimate luxury and only the very rich could afford to buy it. It was such a valuable product its value was likened to that of gold, pearls, exotic spices and musk. Previously in Europe honey was the only way in which food and drinks could be sweetened. The Spanish, Dutch, Portuguese, French and British powers fought with each other to learn about and then gain control over the production of sugar from sugar cane from the Indians and Arabians. They used the techniques they learned and tried them on a larger scale in their new colonies around the world. Cultivating and harvesting sugar cane alone was very labour intensive and needed vast numbers of people whilst the sugar cane itself needed to be grown in well irrigated soil that had a lot of sunlight and heat.

In the 1540s the Portuguese brought sugar cane to be grown in Brazil. They also transported thousands of African slaves to grow the sugar cane on their plantations. By 1550 there were over 3000 small sugar mills across Brazil, Suriname, Demerara (Guyana), Jamaica and Cuba.

In 1625 the Dutch brought sugar cane from South America to the Caribbean islands. They too brought thousands of African slaves to cultivate sugar cane on their plantations from Barbados to the Virgin Islands.

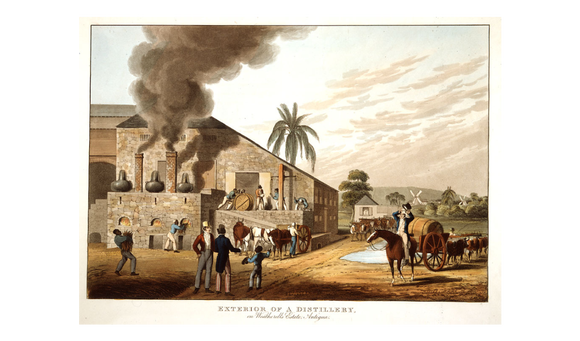

As the number of sugar mills rapidly increased so did the technology to create solid sugar, rum and molasses. This created a big demand for more equipment at the mills including cast iron gears, levers and axles as well as copper cauldrons and stills to boil the sugar cane juice to extract the molasses needed to make rum. These sugar-based products were traded throughout Europe and Africa.

The English, seeing how profitable sugar was as a cash crop in the Caribbean followed the Portuguese and the Dutch to the Caribbean. One such Englishman was James Drax, a wealthy gentleman from Warwickshire, who settled in Barbados in 1625. Initially he used local Native American slaves and white English, Welsh, Irish and Scottish indentured workers on his tobacco plantations. Tobacco had been a very successful cash crop in Virginia and Massachusetts, so Drax hoped for the same in Barbados, but towards the end 1630’s there was a drop in the price of tobacco and the soil and climate were not suited to the crop.

By the 1640s James Drax decided to change his cash crop and learnt how to grow and refine sugar cane from the Dutch colonists who had been taught by the Portuguese. Drax imported equipment such as a triple-roller sugar mill, copper cauldrons, cast iron gears and axels from Holland to make molasses for rum.

This kind of technology was later developed in Britain in the 18th and 19th century by people such as Thomas Patten's Warrington company in Greenfield valley, Thomas Williams of Greenfield Copper & Brass Company and John Wilkinson of Bersham Ironworks. Their sugar processing equipment was exported to plantations across the Caribbean including the Jamaican sugar plantations of the Pennants, a Flintshire family who like Drax profited greatly from the sugar trade but also from the exploitation of African slaves.

Sugar cane is believed to have come from Northern India over 6000 years ago. The word sugar originally came from the Sanskrit shakar meaning “ground or candied” sugar. In ancient India sugar cane juice and sugar products like gur or jaggery were used in food and drink. It was also used in Ayurvedic medicines and in religious Vedic rites and rituals. Indians introduced crystallised sugar to China through Indian Buddhist monks and across the rest of the world through Indian and Arabian merchants and sailors.

During the 14th to 19th century in Europe, sugar was considered to be the ultimate luxury and only the very rich could afford to buy it. It was such a valuable product its value was likened to that of gold, pearls, exotic spices and musk. Previously in Europe honey was the only way in which food and drinks could be sweetened. The Spanish, Dutch, Portuguese, French and British powers fought with each other to learn about and then gain control over the production of sugar from sugar cane from the Indians and Arabians. They used the techniques they learned and tried them on a larger scale in their new colonies around the world. Cultivating and harvesting sugar cane alone was very labour intensive and needed vast numbers of people whilst the sugar cane itself needed to be grown in well irrigated soil that had a lot of sunlight and heat.

In the 1540s the Portuguese brought sugar cane to be grown in Brazil. They also transported thousands of African slaves to grow the sugar cane on their plantations. By 1550 there were over 3000 small sugar mills across Brazil, Suriname, Demerara (Guyana), Jamaica and Cuba.

In 1625 the Dutch brought sugar cane from South America to the Caribbean islands. They too brought thousands of African slaves to cultivate sugar cane on their plantations from Barbados to the Virgin Islands.

As the number of sugar mills rapidly increased so did the technology to create solid sugar, rum and molasses. This created a big demand for more equipment at the mills including cast iron gears, levers and axles as well as copper cauldrons and stills to boil the sugar cane juice to extract the molasses needed to make rum. These sugar-based products were traded throughout Europe and Africa.

The English, seeing how profitable sugar was as a cash crop in the Caribbean followed the Portuguese and the Dutch to the Caribbean. One such Englishman was James Drax, a wealthy gentleman from Warwickshire, who settled in Barbados in 1625. Initially he used local Native American slaves and white English, Welsh, Irish and Scottish indentured workers on his tobacco plantations. Tobacco had been a very successful cash crop in Virginia and Massachusetts, so Drax hoped for the same in Barbados, but towards the end 1630’s there was a drop in the price of tobacco and the soil and climate were not suited to the crop.

By the 1640s James Drax decided to change his cash crop and learnt how to grow and refine sugar cane from the Dutch colonists who had been taught by the Portuguese. Drax imported equipment such as a triple-roller sugar mill, copper cauldrons, cast iron gears and axels from Holland to make molasses for rum.

This kind of technology was later developed in Britain in the 18th and 19th century by people such as Thomas Patten's Warrington company in Greenfield valley, Thomas Williams of Greenfield Copper & Brass Company and John Wilkinson of Bersham Ironworks. Their sugar processing equipment was exported to plantations across the Caribbean including the Jamaican sugar plantations of the Pennants, a Flintshire family who like Drax profited greatly from the sugar trade but also from the exploitation of African slaves.

Flintshire sugar plantation owners

The Pennants arrived in Jamaica when Oliver Cromwell’s British army seized it from the Spanish in 1655. Gifford Pennant a Flintshire man who became a regiment's captain, along with other army men decided to settle in Jamaica, at a time when over three-quarters of the population of West Indies was white and there were very few African slaves. The white population was made up of Irish, Welsh, English, Scottish and other European settlers and indentured servants.

Gifford once settled in Jamaica directed less of his energies towards fighting and more towards turning his landholdings into profitable sugar plantations from which he profited immensely. As a settler, he received land granted in Clarendon, Jamaica in 1665.

There followed a series of acquisitions. In 1669, he was assigned a further 360 acres in the parish and two years later, the Crown granted him three more parcels of land totalling nearly 1,500 acres. By 1670, Gifford Pennant had added more than 2,000 acres, some of which was described as “Savana and scrubby ebonies and wood”. However, this was not all, two years later, he became the owner of 1,500 acres near Lucea, so by the time of his death, Gifford Pennant had 7,327 acres in the parishes of Clarendon and St Elizabeth and became the largest land owner in Jamaica.

At the time of his death Gifford who was also the Assembly member for Clarendon, had a personal estate valued at £2,048 sterling, of which £1,082 was recorded as being made up of slaves. It was recorded that he owned fifty nine slaves – twenty seven men, twenty six women and six children making him one of the largest slave holders inventoried in 1670. His son, Edward Pennant, also an Assembly member, and the Chief Justice of Jamaica, increased his family's wealth. He transformed the Pennant properties into large scale integrated plantations that produced even greater quantities of sugar and other crops. After his death in 1676 he owned a total of 8, 365 acres and his personal property was valued at £29,048 sterling. Such aggressive expansion, however was only able to take place because of the exploitation of a very large labour force of enslaved Africans in Jamaica. Edward Pennant was in fact among the ten largest slave owners in late eighteenth century British America. At his death he owned 610 slaves and of these enslaved people, 271 were adult men, 252 were adult women, 57 were adolescents and 30 were children. These slaves counted for over half of his wealth, valued at £15,538.

The great increase in the number of the Pennant family's slaves, was largely due to a shift in demand for sugar, but also plantation owners' attitudes towards the mixing slaves of different races together on the plantations. Initially white and black slaves worked side by side and were treated as inhumanely as each other but as on tobacco and cotton plantations throughout the Caribbean they were gradually segregated. Fearing insurrection by a combined black and white slave force, white indentured labourers that survived the plantation regime were given overseer jobs and preferential treatment to differentiate themselves from black slaves. Ideas that non-white slaves were inferior due to their lack of Christian beliefs and their appearance were spread also. To really cement the difference, African enslaved men, women and children, unlike previous indentured white slaves, were not given their freedom after completing several years on the plantation, but instead were made to work for the rest of their lives as were their children. This exclusive demand for African slaves saw even greater number of Africans sold into slavery and sent on to ships across the Atlantic Ocean in this period. This accounts for the huge jump in sugar plantation owners’ slave workforce in this era as seen here in the case of the Flintshire Pennants.

Edward's son John Pennant married a Jamaican landowner's daughter Bonella Hodges and gained another 2,000 acres, however they decided along with other immediate family members to enjoy and manage their great wealth in the cooler and more fashionable Hanover Square in London rather than in tropical Jamaica. Known as an absentee landlord, John through written correspondence with his estate managers, managed his estates which were the main source of his wealth. He also however acquired thousands of acres of farmland in England and Wales, which was partially funded from the dividends received from shares held in a number of ships needed to carry his sugar and rum and undoubtedly African slaves.

Richard Pennant, John's son had also before his father' s death scouted domestic prospects for profit in Britain, by marrying Ann Susannah Warburton, an heiress who brought into the family part ownership of a slate quarry in Bethesda near Bangor. With the substantial profits that he made once he had inherited his dead father’s estate, Richard Pennant who became the 1st Baron Penrhyn and MP for Liverpool, turned the Bethesda quarry into a fully-fledged mining enterprise, becoming, in time, the world’s largest slate mine. From a small-scale operation (likened to a farm), it became industrialised, with galleries at different levels allowing 2,000 men to eventually mine 100,000 tons of slate a year. It had its own tramway and seaport to transport the slate for export. 70,000 tiles were for example shipped to Jamaica, for re-roofing the boiler house in Pennant's estate at Kings Valley. This was all made possible through highly skilled white managers and overseers in Jamaica under Richard Pennant's direction, violently traumatising and brutalising plantation born or new African slaves into toiling on the sugar plantations for the Pennant family's profit.

Although unlike their African counterparts, the local Welsh quarrymen of Bethesda had not been torn away from their country and culture by force to toil in the Pennants' quarries, the working conditions for them were also very harsh and exploitative. For this reason, throughout Richard Pennant's successors' control of the quarries, there was a lot of mistrust of them. Edward Gordon Douglas Pennant sacked 80 quarrymen for failing to vote for his son in 1868 when he stood for election as MP for Caernarvonshire. The son, George Douglas Pennant, the 2nd Baron Penrhyn who eventually became a MP, had to endure two prolonged strikes by quarrymen at his quarries. The second beginning in 1900, lasted for three years and was known as "The Great Strike of Penrhyn", the longest dispute in British industrial history. The workers' uprising and the rise of the British Labour Movement caused the steady decline of the North Wales Slate industry and the wealth of the Pennant family in the twentieth century.

Similar revolt and unrest by African slaves in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries led to the end of African slavery. In response to their degrading and inhumane treatment that had caused many slaves to die or even take their own lives, enslaved people en masse rose up and sought to take control of their islands. In Jamaica in 1761 for example in what became known as Tacky's War, the Ashanti, Fante and Akyem enslaved African people under the Fanti warlord Tacky attacked and killed, their masters, overseers and British soldiers. Between 1791 and 1804, self-liberated slaves launched a successful insurrection against French colonial rule in St Domingue (Haiti), which inspired many similar revolts throughout the Caribbean. Finally, between 1831-1832, the largest slave uprising in the British West Indies took place. 60,000 of Jamaica's 300,000 slaves went on strike and then fought in what became known as the Baptist War against British rule. After the revolt was suppressed many slaves who were missionary educated were brutally maimed and executed by the British Jamaican government and plantocracy.

News of these tumultuous events that threatened their businesses and the lives of its managers and overseers on whom their continued commercial success depended upon, would have reached Flintshire's absentee landlords, like the Pennants and the Gladstones. Both families' responses to the criticisms of abolitionists, were predictably unrepentant. In fact, those family members who were members of parliament vigorously defended slavery, on their families' behalf, when its abolition was debated. John Gladstone one of the largest slave owners in the British West Indies by 1833 relied heavily on his MP sons Thomas and most notably William Gladstone, Britain's future Prime Minister for such support.

Gifford once settled in Jamaica directed less of his energies towards fighting and more towards turning his landholdings into profitable sugar plantations from which he profited immensely. As a settler, he received land granted in Clarendon, Jamaica in 1665.

There followed a series of acquisitions. In 1669, he was assigned a further 360 acres in the parish and two years later, the Crown granted him three more parcels of land totalling nearly 1,500 acres. By 1670, Gifford Pennant had added more than 2,000 acres, some of which was described as “Savana and scrubby ebonies and wood”. However, this was not all, two years later, he became the owner of 1,500 acres near Lucea, so by the time of his death, Gifford Pennant had 7,327 acres in the parishes of Clarendon and St Elizabeth and became the largest land owner in Jamaica.

At the time of his death Gifford who was also the Assembly member for Clarendon, had a personal estate valued at £2,048 sterling, of which £1,082 was recorded as being made up of slaves. It was recorded that he owned fifty nine slaves – twenty seven men, twenty six women and six children making him one of the largest slave holders inventoried in 1670. His son, Edward Pennant, also an Assembly member, and the Chief Justice of Jamaica, increased his family's wealth. He transformed the Pennant properties into large scale integrated plantations that produced even greater quantities of sugar and other crops. After his death in 1676 he owned a total of 8, 365 acres and his personal property was valued at £29,048 sterling. Such aggressive expansion, however was only able to take place because of the exploitation of a very large labour force of enslaved Africans in Jamaica. Edward Pennant was in fact among the ten largest slave owners in late eighteenth century British America. At his death he owned 610 slaves and of these enslaved people, 271 were adult men, 252 were adult women, 57 were adolescents and 30 were children. These slaves counted for over half of his wealth, valued at £15,538.

The great increase in the number of the Pennant family's slaves, was largely due to a shift in demand for sugar, but also plantation owners' attitudes towards the mixing slaves of different races together on the plantations. Initially white and black slaves worked side by side and were treated as inhumanely as each other but as on tobacco and cotton plantations throughout the Caribbean they were gradually segregated. Fearing insurrection by a combined black and white slave force, white indentured labourers that survived the plantation regime were given overseer jobs and preferential treatment to differentiate themselves from black slaves. Ideas that non-white slaves were inferior due to their lack of Christian beliefs and their appearance were spread also. To really cement the difference, African enslaved men, women and children, unlike previous indentured white slaves, were not given their freedom after completing several years on the plantation, but instead were made to work for the rest of their lives as were their children. This exclusive demand for African slaves saw even greater number of Africans sold into slavery and sent on to ships across the Atlantic Ocean in this period. This accounts for the huge jump in sugar plantation owners’ slave workforce in this era as seen here in the case of the Flintshire Pennants.

Edward's son John Pennant married a Jamaican landowner's daughter Bonella Hodges and gained another 2,000 acres, however they decided along with other immediate family members to enjoy and manage their great wealth in the cooler and more fashionable Hanover Square in London rather than in tropical Jamaica. Known as an absentee landlord, John through written correspondence with his estate managers, managed his estates which were the main source of his wealth. He also however acquired thousands of acres of farmland in England and Wales, which was partially funded from the dividends received from shares held in a number of ships needed to carry his sugar and rum and undoubtedly African slaves.

Richard Pennant, John's son had also before his father' s death scouted domestic prospects for profit in Britain, by marrying Ann Susannah Warburton, an heiress who brought into the family part ownership of a slate quarry in Bethesda near Bangor. With the substantial profits that he made once he had inherited his dead father’s estate, Richard Pennant who became the 1st Baron Penrhyn and MP for Liverpool, turned the Bethesda quarry into a fully-fledged mining enterprise, becoming, in time, the world’s largest slate mine. From a small-scale operation (likened to a farm), it became industrialised, with galleries at different levels allowing 2,000 men to eventually mine 100,000 tons of slate a year. It had its own tramway and seaport to transport the slate for export. 70,000 tiles were for example shipped to Jamaica, for re-roofing the boiler house in Pennant's estate at Kings Valley. This was all made possible through highly skilled white managers and overseers in Jamaica under Richard Pennant's direction, violently traumatising and brutalising plantation born or new African slaves into toiling on the sugar plantations for the Pennant family's profit.

Although unlike their African counterparts, the local Welsh quarrymen of Bethesda had not been torn away from their country and culture by force to toil in the Pennants' quarries, the working conditions for them were also very harsh and exploitative. For this reason, throughout Richard Pennant's successors' control of the quarries, there was a lot of mistrust of them. Edward Gordon Douglas Pennant sacked 80 quarrymen for failing to vote for his son in 1868 when he stood for election as MP for Caernarvonshire. The son, George Douglas Pennant, the 2nd Baron Penrhyn who eventually became a MP, had to endure two prolonged strikes by quarrymen at his quarries. The second beginning in 1900, lasted for three years and was known as "The Great Strike of Penrhyn", the longest dispute in British industrial history. The workers' uprising and the rise of the British Labour Movement caused the steady decline of the North Wales Slate industry and the wealth of the Pennant family in the twentieth century.

Similar revolt and unrest by African slaves in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries led to the end of African slavery. In response to their degrading and inhumane treatment that had caused many slaves to die or even take their own lives, enslaved people en masse rose up and sought to take control of their islands. In Jamaica in 1761 for example in what became known as Tacky's War, the Ashanti, Fante and Akyem enslaved African people under the Fanti warlord Tacky attacked and killed, their masters, overseers and British soldiers. Between 1791 and 1804, self-liberated slaves launched a successful insurrection against French colonial rule in St Domingue (Haiti), which inspired many similar revolts throughout the Caribbean. Finally, between 1831-1832, the largest slave uprising in the British West Indies took place. 60,000 of Jamaica's 300,000 slaves went on strike and then fought in what became known as the Baptist War against British rule. After the revolt was suppressed many slaves who were missionary educated were brutally maimed and executed by the British Jamaican government and plantocracy.

News of these tumultuous events that threatened their businesses and the lives of its managers and overseers on whom their continued commercial success depended upon, would have reached Flintshire's absentee landlords, like the Pennants and the Gladstones. Both families' responses to the criticisms of abolitionists, were predictably unrepentant. In fact, those family members who were members of parliament vigorously defended slavery, on their families' behalf, when its abolition was debated. John Gladstone one of the largest slave owners in the British West Indies by 1833 relied heavily on his MP sons Thomas and most notably William Gladstone, Britain's future Prime Minister for such support.

In the early nineteenth century Scotsman, John Gladstone was a successful Liverpool based merchant who traded corn, cotton and sugar in America, Brazil, Russia and India. He soon realised that sugar was becoming the fastest growing commodity and bought large plots of land to develop sugar estates in Jamaica and Demerara, Guyana. He soon rose up the ranks to become the chairman of the powerful West India Association. By the time slavery was formally abolished in 1833 his estates were worth £336,000, over £40million in today’s money. His financially lucrative plantations, however were also subject to attack.

In 1823 a massive slave revolt, known as the Demerara rebellion on his plantation, saw 10,000 enslaved people express their desire for freedom and rise up in protest over their poor treatment. The execution of a white English pastor, John Smith, believed to be one of the ringleaders of the rebellion strengthened the abolitionist movement and led to more passionate debate in the British Parliament. William Gladstone, John Gladstone's younger MP son, while admitting his “deep, though indirect, pecuniary interest” argued in the house that the emancipation of slaves would undermine sugar production and that plantation owners should, if slavery was abolished, receive just compensation. The British government, further lobbied by West India proprietors agreed to award compensation of £20million pounds, of which John Gladstone received the largest share; £106,769 in official reimbursement for the 2,508 slaves he owned across nine plantations in the Caribbean.

William Gladstone later inherited some of his father’s slavery based wealth which he invested partially in renovating and buying land around Hawarden Castle in Flintshire. Although, it has been argued that William Gladstone in his speeches admitted that there had been acts of cruelty against slaves and that their welfare was paramount, his attitude still reflected those of his father’s, that slaves were inferior due to their race and needed to be occupied in work under Christian guidance. For this reason, Gladstone strongly welcomed the apprenticeship system, that replaced slavery, a system that obliged former enslaved people to work for their former slave owners for free or face punishment if they did not. It is not surprising that many people in the Caribbean and Britain saw the apprenticeship system as a continuation of slavery in many ways. Their protests, helped bring about its end for all apprenticed, former slaves in 1838.

John Gladstone having lost his former slaves and apprentices turned to India for workers to work on his sugar plantations. Knowing that a number of Indians had been sent as indentured labour to the British colony island of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean by the British government. Gladstone was the first to express a desire to obtain free labour from India for his plantations in the West Indies. The conditions imposed on these Indian indentured labourers however were so appalling that they fled in numbers. This didn't stop the British government from sending more Indian labourers to the Caribbean and South America once the floodgates were opened by Gladstone.

Between 1838 and 1917 well over half a million Indians were sent to toil the sugar cane plantation fields in the West Indies. The horrendous conditions and restrictions they lived under prompted many Indian nationalists and Vedic (Hindu) missionaries who lived among the Indian diaspora to fight for the end of the indentured labour system. The system of indentured labour was officially abolished by the British government in 1917.

As with the African slaves of the West Indies, the Welsh quarrymen of Penrhyn, the oppressed Indian indentured labourers eventually managed to successfully throw off the sugar plantation and imperialist shackles that bound them. What is poignant however is that very few today are aware of the bitter-sweet international story of enslavement and suffering and the not so insignificant part North Wales and prominent families from Flintshire in particular had to play in this. This is despite the towering existence of buildings such as Penrhyn Castle, the ruined works at Greenfield Valley, Greenfield Docks and the cavernous Penrhyn quarries and all the major roads and related infrastructure which were funded ironically by the sweetest of all substances - sugar.

In 1823 a massive slave revolt, known as the Demerara rebellion on his plantation, saw 10,000 enslaved people express their desire for freedom and rise up in protest over their poor treatment. The execution of a white English pastor, John Smith, believed to be one of the ringleaders of the rebellion strengthened the abolitionist movement and led to more passionate debate in the British Parliament. William Gladstone, John Gladstone's younger MP son, while admitting his “deep, though indirect, pecuniary interest” argued in the house that the emancipation of slaves would undermine sugar production and that plantation owners should, if slavery was abolished, receive just compensation. The British government, further lobbied by West India proprietors agreed to award compensation of £20million pounds, of which John Gladstone received the largest share; £106,769 in official reimbursement for the 2,508 slaves he owned across nine plantations in the Caribbean.

William Gladstone later inherited some of his father’s slavery based wealth which he invested partially in renovating and buying land around Hawarden Castle in Flintshire. Although, it has been argued that William Gladstone in his speeches admitted that there had been acts of cruelty against slaves and that their welfare was paramount, his attitude still reflected those of his father’s, that slaves were inferior due to their race and needed to be occupied in work under Christian guidance. For this reason, Gladstone strongly welcomed the apprenticeship system, that replaced slavery, a system that obliged former enslaved people to work for their former slave owners for free or face punishment if they did not. It is not surprising that many people in the Caribbean and Britain saw the apprenticeship system as a continuation of slavery in many ways. Their protests, helped bring about its end for all apprenticed, former slaves in 1838.

John Gladstone having lost his former slaves and apprentices turned to India for workers to work on his sugar plantations. Knowing that a number of Indians had been sent as indentured labour to the British colony island of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean by the British government. Gladstone was the first to express a desire to obtain free labour from India for his plantations in the West Indies. The conditions imposed on these Indian indentured labourers however were so appalling that they fled in numbers. This didn't stop the British government from sending more Indian labourers to the Caribbean and South America once the floodgates were opened by Gladstone.

Between 1838 and 1917 well over half a million Indians were sent to toil the sugar cane plantation fields in the West Indies. The horrendous conditions and restrictions they lived under prompted many Indian nationalists and Vedic (Hindu) missionaries who lived among the Indian diaspora to fight for the end of the indentured labour system. The system of indentured labour was officially abolished by the British government in 1917.

As with the African slaves of the West Indies, the Welsh quarrymen of Penrhyn, the oppressed Indian indentured labourers eventually managed to successfully throw off the sugar plantation and imperialist shackles that bound them. What is poignant however is that very few today are aware of the bitter-sweet international story of enslavement and suffering and the not so insignificant part North Wales and prominent families from Flintshire in particular had to play in this. This is despite the towering existence of buildings such as Penrhyn Castle, the ruined works at Greenfield Valley, Greenfield Docks and the cavernous Penrhyn quarries and all the major roads and related infrastructure which were funded ironically by the sweetest of all substances - sugar.

References

- Journal article- THE CONDITION OF THE SLAVES ON THE SUGAR PLANTATIONS OF SIR JOHN GLADSTONE IN THE COLONY OF DEMERARA, 1812-49 By Richard B. Sheridan https://www.jstor.org/stable/41850197?seq=1

- Journal article -Gladstone and Slavery https://www.jstor.org/stable/40264175?seq=1

- Anthony Gambrill | Jamaica in Britain: the legacy of slavery and sugar

- http://jamaica-gleaner.com/article/focus/20160603/anthony-gambrill-jamaica-britain-legacy-slavery-and-sugar-part-3

- H.V. Bowen (edited), Wales and the British overseas empire: Interactions and influences, 1650–1830 https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=YW8CEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA118&lpg=PA118&dq=pennant+exploitation+Penrhyn+quarry&source=bl&ots=yYEE1h5Gv0&sig=ACfU3U2arqzT6UXVZPESrRM-JLtS_YHlPg&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjdgrH85NXvAhVvShUIHXUgB284FBDoATAHegQIExAD#v=onepage&q=pennant%20exploitation%20Penrhyn%20quarry&f=false

Get in touchRegistered charity no. 1116970

Email: [email protected] Telephone: 01492 622233 The Equality Centre Bangor Road Penmaenmawr Conwy LL34 6LF |