Are you wearing something made of cotton?

History of Cotton

A cotton field

A cotton field

During the late 18th and early 19th centuries the cotton industry accounted for over 40 per cent of all exports from Britain. It brought millions of pounds into the country which paid for the development of good roads and housing and which we all take for granted nowadays.

Cotton was at the heart of the British industrial revolution. Initially cotton textiles were made in India, by Indians and these were traded in Britain by the East India company (EIC). As British men and women developed a taste for beautifully printed and embroidered, cheaper more affordable and versatile cotton clothing, EIC’s commercial activities increased. In order to the break the Indian merchants’ monopoly on the market the EIC travelled to India in the 17th and 18th century. There they gained control over local governments and exploited thousands of Indian farmers and weavers by forcing them to supply the world with raw cotton and cotton textiles through only the EIC. The huge wealth that was generated from the Indian cotton industry as well as from the looting and plundering of other precious items from it, financed much of Britain's industrial revolution.

While the Calico Acts of 1700 and 1721, enacted by parliament attempted to stop the EIC from destroying the British wool and linen trade by flooding the market with cheap Indian cotton cloth, it also served as a spur for the creation of a domestic cotton clothing industry. The Calico Acts prohibited most Indian cotton goods from being imported or sold in the country, with the exception of raw cotton, which could be imported for producing cotton clothing in Britain for the home market. India began to provide Britain's new cotton clothes manufacturing industry with the raw cotton it needed. As the demand for cotton textiles continued to grow in Britain, this triggered the invention of machines such as the spinning jenny, the water frame, the spinning mule and the power loom which increased the speed and size of production in British cotton mills.

Between 1770 and 1801 raw cotton continued to be imported from India by the EIC. It exploited poor Indian farmers across the country making them pay ridiculously high land and trade taxes which between 1769 and 1773 led to many famines, especially in cotton producing Bengal. As a result of the famines, 10 million people died of starvation. Despite, this horrific situation, the EIC relentlessly shipped hundreds of thousands of bales of cotton to help Britain's cotton and related industries boom.

Cotton was at the heart of the British industrial revolution. Initially cotton textiles were made in India, by Indians and these were traded in Britain by the East India company (EIC). As British men and women developed a taste for beautifully printed and embroidered, cheaper more affordable and versatile cotton clothing, EIC’s commercial activities increased. In order to the break the Indian merchants’ monopoly on the market the EIC travelled to India in the 17th and 18th century. There they gained control over local governments and exploited thousands of Indian farmers and weavers by forcing them to supply the world with raw cotton and cotton textiles through only the EIC. The huge wealth that was generated from the Indian cotton industry as well as from the looting and plundering of other precious items from it, financed much of Britain's industrial revolution.

While the Calico Acts of 1700 and 1721, enacted by parliament attempted to stop the EIC from destroying the British wool and linen trade by flooding the market with cheap Indian cotton cloth, it also served as a spur for the creation of a domestic cotton clothing industry. The Calico Acts prohibited most Indian cotton goods from being imported or sold in the country, with the exception of raw cotton, which could be imported for producing cotton clothing in Britain for the home market. India began to provide Britain's new cotton clothes manufacturing industry with the raw cotton it needed. As the demand for cotton textiles continued to grow in Britain, this triggered the invention of machines such as the spinning jenny, the water frame, the spinning mule and the power loom which increased the speed and size of production in British cotton mills.

Between 1770 and 1801 raw cotton continued to be imported from India by the EIC. It exploited poor Indian farmers across the country making them pay ridiculously high land and trade taxes which between 1769 and 1773 led to many famines, especially in cotton producing Bengal. As a result of the famines, 10 million people died of starvation. Despite, this horrific situation, the EIC relentlessly shipped hundreds of thousands of bales of cotton to help Britain's cotton and related industries boom.

Flintshire's Cotton Mills

Cotton Twist Company - Greenfield Valley

Cotton mills in Flintshire would undoubtedly have received a lot of this Indian cotton produced through exploitation, through its Greenfield docks as well as others along the Dee estuary. In 1770, cotton mills powered by water wheels began to appear across Britain's North West, including North East Wales. In Greenfield Valley two prominent English businessmen, John Smalley and John Chambers created the Cotton Twist Company. Yellow Mill was their first factory, built next to Basingwerk Abbey, using some of the stones taken from the abbey, it was a small mill only three stories high which was powered by a fifteen-foot-tall water wheel. Yellow mill looked like a typical Lancashire warehouse of that time. Most of the workers were brought in from England as they had experience working in other mills and didn’t need to be trained.

By the early 1770s pressure from mill owners like John Smalley and John Chambers, who wanted to compete with the East India Company for the British and international cotton market, saw Parliament repealing the Calico Act. After this happened in 1774 this triggered an influx of investments into domestic cotton production.

From the mid-1790s, however the production of raw cotton switched from India to the United States which led to thousands more Africans slaves being transported to work on the cotton fields in the American South states of Alabama, Mississippi, Georgia and Louisiana. British merchants continued to profit the most from trading black men, women and children across the Atlantic sea from Western Africa to the newly independent United States. Slaves were treated worse than the livestock used on the plantations. They were over worked, under fed and often violently tortured or killed in gruesome ways if they tried to run away or fight for their freedom.

The cotton mills in the Greenfield Valley and in Mold, sadly helped the cruel system of slavery grow and develop into an industry worth millions which in today's money would be billions.

When John Smalley died in 1782, his widow and son Christopher Smalley inherited his shares in the Cotton Twist Company. Almost immediately after John Chambers became bankrupt he left the company and the Smalley family brought in new business partners. They attracted some of the leading cotton manufacturers of the time to invest including William Douglas of Salford, Daniel and John Whittaker of Manchester, Ann, John and Jonathan Dumbell of Warrington and John Douglas of Pendleton. It is not surprising that with the combined expertise of these new but very experienced partners, business boomed.

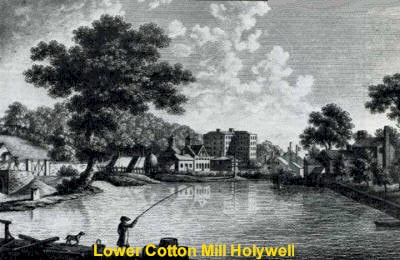

By 1790 the company had built three more mills in the Greenfield Valley, Upper Cotton Mill in 1783 and Lower Cotton Mill in 1785 and Crescent Mill in 1790. The Upper was built in six weeks and Lower mill was constructed within ten weeks both mills were six storeys high which clearly indicates just how fast the cotton manufacturing industry was growing and how much profit they must have made. The company’s success could even be seen outside of Greenfield Valley. Outworkers were employed at Ysceifiog, Newmarket (now Trelawnyd) and Denbigh to pick and sort raw cotton. This was done in an old Denbigh woollen mill built by Mostyn, Pigot & Co in 1749 which the Holywell Company had taken over.

William and Thomas Douglas were helped by Peter Atherton to construct and equip the cotton mills at Holywell where he became the senior partner. In 1790 Atherton designed and erected the Mold cotton mill. He famously aided Richard Arkwright in the creation of a working model of a spinning machine and was an advocate for the use of steam power in mills.

By 1795 William Douglas insured the Holywell Company and his Manchester mills at a value of £80,950 (approximately £10 million today). It was the second highest valued company in Britain at that time. According to Thomas Pennant (a travel writer and distant cousin of Richard Pennant) the Holywell mills employed over 1,225 people including 500 women and children, as well as 300 parish apprentices who were housed nearby in the company’s own housing which was described by Pennant as being “commodious” – comfortable and roomy.

In those days it wasn’t uncommon for children as young at 4 years old to be working in the cotton mills. This was because they could fit into small spaces to clean waste cotton that had fallen on the floor in between the spinning mules. Parish apprentices who were orphaned or very poor children living in the work houses, were forced by the parish to work for free in exchange for very basic food and accommodation at the cotton mills. They were compelled to do so until they reached the age of 18 or 21 years old as the parish had often signed their indenture papers without their knowledge when they were young children.

Adult mill workers were often housed in terraced buildings, built and owned by the company next to the factories so that their days revolved around their work. Working conditions for the men, women and children in textile mills were generally awful with long 18 hour working days and very low wages. These conditions drove many to an early death from malnutrition and health complications like asthma and lung disease from breathing in the fine fibres from the cotton. The working and living conditions in the cotton company were so bad that many tried to escape their daily drudgery. In 1791 four “articled servants” or indentured apprentices working as mule-spinners ran away from the factory. Three of them were from the local area.

Eli Whitney’s invention of the cotton gin machine in Massachusetts, America in 1793 changed the face of American raw cotton production. The cotton gin machine could remove the seeds from the cotton fibres. This process had previously been a done manually and was very labour intensive and time consuming. The cotton gin made it possible to create cotton bales ten times faster and cheaper than before which meant that more cotton could be exported to Britain for spinning and weaving. In 1791 the U.S. had only produced 900 thousand kilograms of cotton but by 1801 the country was producing over 22 million kilograms and this was undoubtedly due to the introduction of the cotton gin on cotton plantations in the South. By the 1830s the United States had taken over from India as the world's biggest cotton exporter.

Growing cotton itself was a very tough work so the white owners brought thousands of black slaves to work relentlessly on the large plantations. The slaves brought in huge profits for the owners who became some of the wealthiest men in America. The vast majority of American cotton was shipped over to the port of Liverpool, which was close to the cotton mills of Lancashire and Flintshire. Cotton was transported from Liverpool to Greenfield harbour and up the valley to be spun in the Cotton Twist Company’s four mills. According to Samuel Lewis’s Topographical Dictionary (1833) the company in Holywell relied heavily on Richard Arkwright’s spinning and water frames inventions to increase its production rates and profits. There were 12,218 spindles in the Upper Mill, 7,492 in the Lower Mill and 8,286 in the Crescent Mill which collectively produced 26,096 pounds of thread per week.

In 1835 the mills in Greenfield Valley introduced five of James Watt’s steam engines and four large water wheels. These were the height of modern industrial technology at that time, and they were needed in order to compete with the rapid pace of production in Lancashire.

Despite the introduction of modern technology, the mills in Holywell struggled to keep up with its competitors and in 1837 the cotton market slumped which led to the gradual decline of the Douglas family who were by now the main shareholders in Douglas & Co. after Christopher Smalley and his family had left in 1828.

The company was in such decline that when in 1837 a Factory Inspector, T. Jones Howell unexpectedly visited two of the cotton mills in Holywell between 10 pm and midnight, he stated that “I never saw any set of people so wan and haggard in their appearance as those who were then and there at work” The company were prosecuted and fined £19 on several charges including one for employing persons under 18 years for excessive hours.

By 1841 Douglas & Co. employed just 14 cotton spinners and went into liquidation.

Cotton mills in Flintshire would undoubtedly have received a lot of this Indian cotton produced through exploitation, through its Greenfield docks as well as others along the Dee estuary. In 1770, cotton mills powered by water wheels began to appear across Britain's North West, including North East Wales. In Greenfield Valley two prominent English businessmen, John Smalley and John Chambers created the Cotton Twist Company. Yellow Mill was their first factory, built next to Basingwerk Abbey, using some of the stones taken from the abbey, it was a small mill only three stories high which was powered by a fifteen-foot-tall water wheel. Yellow mill looked like a typical Lancashire warehouse of that time. Most of the workers were brought in from England as they had experience working in other mills and didn’t need to be trained.

By the early 1770s pressure from mill owners like John Smalley and John Chambers, who wanted to compete with the East India Company for the British and international cotton market, saw Parliament repealing the Calico Act. After this happened in 1774 this triggered an influx of investments into domestic cotton production.

From the mid-1790s, however the production of raw cotton switched from India to the United States which led to thousands more Africans slaves being transported to work on the cotton fields in the American South states of Alabama, Mississippi, Georgia and Louisiana. British merchants continued to profit the most from trading black men, women and children across the Atlantic sea from Western Africa to the newly independent United States. Slaves were treated worse than the livestock used on the plantations. They were over worked, under fed and often violently tortured or killed in gruesome ways if they tried to run away or fight for their freedom.

The cotton mills in the Greenfield Valley and in Mold, sadly helped the cruel system of slavery grow and develop into an industry worth millions which in today's money would be billions.

When John Smalley died in 1782, his widow and son Christopher Smalley inherited his shares in the Cotton Twist Company. Almost immediately after John Chambers became bankrupt he left the company and the Smalley family brought in new business partners. They attracted some of the leading cotton manufacturers of the time to invest including William Douglas of Salford, Daniel and John Whittaker of Manchester, Ann, John and Jonathan Dumbell of Warrington and John Douglas of Pendleton. It is not surprising that with the combined expertise of these new but very experienced partners, business boomed.

By 1790 the company had built three more mills in the Greenfield Valley, Upper Cotton Mill in 1783 and Lower Cotton Mill in 1785 and Crescent Mill in 1790. The Upper was built in six weeks and Lower mill was constructed within ten weeks both mills were six storeys high which clearly indicates just how fast the cotton manufacturing industry was growing and how much profit they must have made. The company’s success could even be seen outside of Greenfield Valley. Outworkers were employed at Ysceifiog, Newmarket (now Trelawnyd) and Denbigh to pick and sort raw cotton. This was done in an old Denbigh woollen mill built by Mostyn, Pigot & Co in 1749 which the Holywell Company had taken over.

William and Thomas Douglas were helped by Peter Atherton to construct and equip the cotton mills at Holywell where he became the senior partner. In 1790 Atherton designed and erected the Mold cotton mill. He famously aided Richard Arkwright in the creation of a working model of a spinning machine and was an advocate for the use of steam power in mills.

By 1795 William Douglas insured the Holywell Company and his Manchester mills at a value of £80,950 (approximately £10 million today). It was the second highest valued company in Britain at that time. According to Thomas Pennant (a travel writer and distant cousin of Richard Pennant) the Holywell mills employed over 1,225 people including 500 women and children, as well as 300 parish apprentices who were housed nearby in the company’s own housing which was described by Pennant as being “commodious” – comfortable and roomy.

In those days it wasn’t uncommon for children as young at 4 years old to be working in the cotton mills. This was because they could fit into small spaces to clean waste cotton that had fallen on the floor in between the spinning mules. Parish apprentices who were orphaned or very poor children living in the work houses, were forced by the parish to work for free in exchange for very basic food and accommodation at the cotton mills. They were compelled to do so until they reached the age of 18 or 21 years old as the parish had often signed their indenture papers without their knowledge when they were young children.

Adult mill workers were often housed in terraced buildings, built and owned by the company next to the factories so that their days revolved around their work. Working conditions for the men, women and children in textile mills were generally awful with long 18 hour working days and very low wages. These conditions drove many to an early death from malnutrition and health complications like asthma and lung disease from breathing in the fine fibres from the cotton. The working and living conditions in the cotton company were so bad that many tried to escape their daily drudgery. In 1791 four “articled servants” or indentured apprentices working as mule-spinners ran away from the factory. Three of them were from the local area.

Eli Whitney’s invention of the cotton gin machine in Massachusetts, America in 1793 changed the face of American raw cotton production. The cotton gin machine could remove the seeds from the cotton fibres. This process had previously been a done manually and was very labour intensive and time consuming. The cotton gin made it possible to create cotton bales ten times faster and cheaper than before which meant that more cotton could be exported to Britain for spinning and weaving. In 1791 the U.S. had only produced 900 thousand kilograms of cotton but by 1801 the country was producing over 22 million kilograms and this was undoubtedly due to the introduction of the cotton gin on cotton plantations in the South. By the 1830s the United States had taken over from India as the world's biggest cotton exporter.

Growing cotton itself was a very tough work so the white owners brought thousands of black slaves to work relentlessly on the large plantations. The slaves brought in huge profits for the owners who became some of the wealthiest men in America. The vast majority of American cotton was shipped over to the port of Liverpool, which was close to the cotton mills of Lancashire and Flintshire. Cotton was transported from Liverpool to Greenfield harbour and up the valley to be spun in the Cotton Twist Company’s four mills. According to Samuel Lewis’s Topographical Dictionary (1833) the company in Holywell relied heavily on Richard Arkwright’s spinning and water frames inventions to increase its production rates and profits. There were 12,218 spindles in the Upper Mill, 7,492 in the Lower Mill and 8,286 in the Crescent Mill which collectively produced 26,096 pounds of thread per week.

In 1835 the mills in Greenfield Valley introduced five of James Watt’s steam engines and four large water wheels. These were the height of modern industrial technology at that time, and they were needed in order to compete with the rapid pace of production in Lancashire.

Despite the introduction of modern technology, the mills in Holywell struggled to keep up with its competitors and in 1837 the cotton market slumped which led to the gradual decline of the Douglas family who were by now the main shareholders in Douglas & Co. after Christopher Smalley and his family had left in 1828.

The company was in such decline that when in 1837 a Factory Inspector, T. Jones Howell unexpectedly visited two of the cotton mills in Holywell between 10 pm and midnight, he stated that “I never saw any set of people so wan and haggard in their appearance as those who were then and there at work” The company were prosecuted and fined £19 on several charges including one for employing persons under 18 years for excessive hours.

By 1841 Douglas & Co. employed just 14 cotton spinners and went into liquidation.

Mold cotton mill

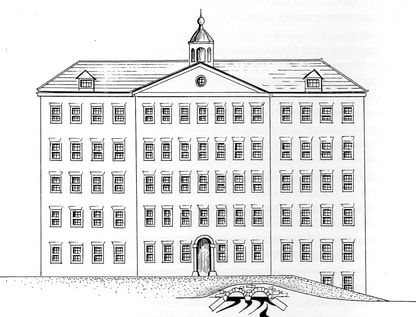

Due to the early success of the Cotton Twist Company in the 1790s, Lancashire manufacturers flooded into North East Wales in search of similar profit-making opportunities. The Mold cotton mill was built on an old lead mining site next to the River Alyn which had all the infrastructure with access to water and coal in place.

In 1800 the mill in Mold was fully functioning and up for sale by Messrs Hodson and Leigh who were well known cotton spinners in Manchester and Stockport. The advertisement stated that the mill at this date “is in full work, having a competent number of excellent hands, and the mill as in complete repair and fully equipped with water, and the machinery is in excellent condition upon the most improved principles”. It included stables, barns and sixteen red-brick cottages at Rhydygoleu which previously housed the lead-miners. The machinery included “4000 spindles and all the necessary geers, tumbling shafts, water wheels” which evidently describe “a handsome and stupendous factory”.

The factory passed through several English owners who went through turbulent financial times but in the 1830s Messrs Unman and Son took over the business and introduced steam engines and power-looms for weaving calico cloths which brought a period of great prosperity to the area.

With the growth of the company came the need for more housing for the larger numbers of workers coming from the local area as well as from Manchester and other parts of Lancashire. In 1834 a school was built for the children working in the mill. By 1846 there were over thirty children attending the school.

At its height the Mold cotton company employed 250 and had 25,000 spindles. It survived the Cotton Famine during the American Civil War but it burned down in 1866 and was never rebuilt. In 1874 the estate was in ruins and was bought over by a steel tinplate company.

History seems to have forgotten the key role that industries in Flintshire had in the creation of the British Empire and the British cotton Industrial Revolution. Both of these powerful oppressive systems were only made possible because of the exploitative importation of raw cotton from India and later America.

India had initially supplied England and Europe with colourful cotton textiles which gave its people the taste for new fashion that was more versatile than the woollen and linen clothing that they had previously been wearing. European merchants competed with one another to do trade with India and started to set up their own companies that were given the right to rule over large parts of India. Many poor Indian farmers were then exploited and starved to death by the East India Company’s tyrannical tax system. Meanwhile Africans were kidnapped and transported thousands of miles from their homes to work and live in horrendous conditions to grow cotton as a cash crop. The Indian and Africans were not the only ones who were exploited and treated badly, poor British workers were also treated horrendously. They were often forced into indenture and made to work long hours under terrible conditions in the Flintshire cotton mills and across the North West of England.

The effects of exploitation were being felt by the poor and vulnerable across the world and it was the middle-classes and the upper-classes who benefitted the most from the Industrial Revolution.

Due to the early success of the Cotton Twist Company in the 1790s, Lancashire manufacturers flooded into North East Wales in search of similar profit-making opportunities. The Mold cotton mill was built on an old lead mining site next to the River Alyn which had all the infrastructure with access to water and coal in place.

In 1800 the mill in Mold was fully functioning and up for sale by Messrs Hodson and Leigh who were well known cotton spinners in Manchester and Stockport. The advertisement stated that the mill at this date “is in full work, having a competent number of excellent hands, and the mill as in complete repair and fully equipped with water, and the machinery is in excellent condition upon the most improved principles”. It included stables, barns and sixteen red-brick cottages at Rhydygoleu which previously housed the lead-miners. The machinery included “4000 spindles and all the necessary geers, tumbling shafts, water wheels” which evidently describe “a handsome and stupendous factory”.

The factory passed through several English owners who went through turbulent financial times but in the 1830s Messrs Unman and Son took over the business and introduced steam engines and power-looms for weaving calico cloths which brought a period of great prosperity to the area.

With the growth of the company came the need for more housing for the larger numbers of workers coming from the local area as well as from Manchester and other parts of Lancashire. In 1834 a school was built for the children working in the mill. By 1846 there were over thirty children attending the school.

At its height the Mold cotton company employed 250 and had 25,000 spindles. It survived the Cotton Famine during the American Civil War but it burned down in 1866 and was never rebuilt. In 1874 the estate was in ruins and was bought over by a steel tinplate company.

History seems to have forgotten the key role that industries in Flintshire had in the creation of the British Empire and the British cotton Industrial Revolution. Both of these powerful oppressive systems were only made possible because of the exploitative importation of raw cotton from India and later America.

India had initially supplied England and Europe with colourful cotton textiles which gave its people the taste for new fashion that was more versatile than the woollen and linen clothing that they had previously been wearing. European merchants competed with one another to do trade with India and started to set up their own companies that were given the right to rule over large parts of India. Many poor Indian farmers were then exploited and starved to death by the East India Company’s tyrannical tax system. Meanwhile Africans were kidnapped and transported thousands of miles from their homes to work and live in horrendous conditions to grow cotton as a cash crop. The Indian and Africans were not the only ones who were exploited and treated badly, poor British workers were also treated horrendously. They were often forced into indenture and made to work long hours under terrible conditions in the Flintshire cotton mills and across the North West of England.

The effects of exploitation were being felt by the poor and vulnerable across the world and it was the middle-classes and the upper-classes who benefitted the most from the Industrial Revolution.

References

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_cotton

- Edward J. Foulkes, The cotton-spinning factories of Flintshire 1777-1866 https://www.themeister.co.uk/hindley/flintshire_cotton.pdf

- https://www.gracesguide.co.uk/John_Smalley_(c.1729-1782)

- http://www.douglashistory.co.uk/history/Businesses/cotton_twist_company.html#.YBvoROj7Q2w

- Cotton Mill ruins photos courtsey of Ffilmiau Cymunedol Davies Community Films

Get in touchRegistered charity no. 1116970

Email: [email protected] Telephone: 01492 622233 The Equality Centre Bangor Road Penmaenmawr Conwy LL34 6LF |